New horizons

New horizons

Science and scholarship yield new insights and sometimes even lead us to see a specific subject area with completely different eyes, fostering new knowledge and understanding. For example, in the University’s early years, the first female German studies professor, Agathe Lasch, shed new light on language by looking at social relationships and cultural influences. Her contemporary, Erwin Panofsky, the “Einstein of Art History,” no longer interpreted artworks by looking solely at their formal properties but at their cultural and historical contexts as well.

The Hamburg School of Art History

Interpreting artworks with the aid of all available resources, including historical sources, formed the core of Erwin Panofsky’s approach to art history, known as “iconology.” This approach includes the analysis of formal properties that had previously been seen as the only valid approach to interpreting art. Panofsky developed his three-stage system of interpretation in Hamburg, where he headed the Art History Seminar, founded in 1921. Here, he met Aby Warburg—and discovered his Warburg Library of Cultural Studies—the philosopher Ernst Cassirer, and a group of motivated students. The Nazis forced him out in 1933 and Panofsky emigrated to the US. Sixty years later, Martin Warnke continued the Hamburg’s School’s tradition.

Warburg-Archiv im Warburg-Haus

Seminar excursion (Erwin Panofsky, smoking, third from right), ca. 1930

“… to place the word in life.”

With this socio-linguistic research motto, Agathe Lasch was ahead of her time. Applying it to her own subject area, lower German linguistics and literature, Lasch looked at linguistic change by studying not just phonemes but society, culture, and politics. The University can thank its first female professor for two influential dictionaries and several more pioneering publications. Because she was Jewish, this visionary urban linguist and researcher was forced to leave the University in 1934. Agathe Lasch was murdered by the National Socialists in 1942.

Satu Helomaa, Kauniainen, Finnland (aus dem Nachlass von Martta Jaatinen)

Agathe Lasch in her apartment in today’s Gustav-Leo-Straße 9, 1930

Brilliant teacher: Erwin Panofsky (1892–1968)

As late as 1964 Panofsky wrote, “… and the enthusiasm of the students, who had, almost without exception, stayed true to the tradition of the Hamburg School from beginning to end, was one-of-a-kind.“ The photo shows Panofsky, his wife, and his special bond to his students.

Warburg-Archiv im Warburg-Haus, Hamburg

Seminar excursion (Erwin Panofsky, smoking, third from right), ca. 1930

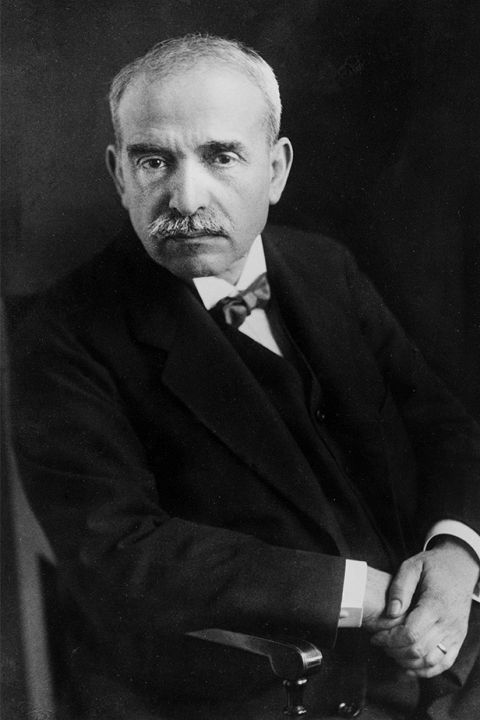

Visionary private tutor: Aby Warburg (1866–1929)

When Warburg noticed that visual motifs from antiquity resurfaced in later epochs, he concluded that one must know the history of motifs and their meanings in their respective eras in order to really grasp an artwork. In 1912, the art historian and professor coined the word “iconology” for this approach.

Warburg-Institute Archive, London

Portrait of Aby Warburg, 1925

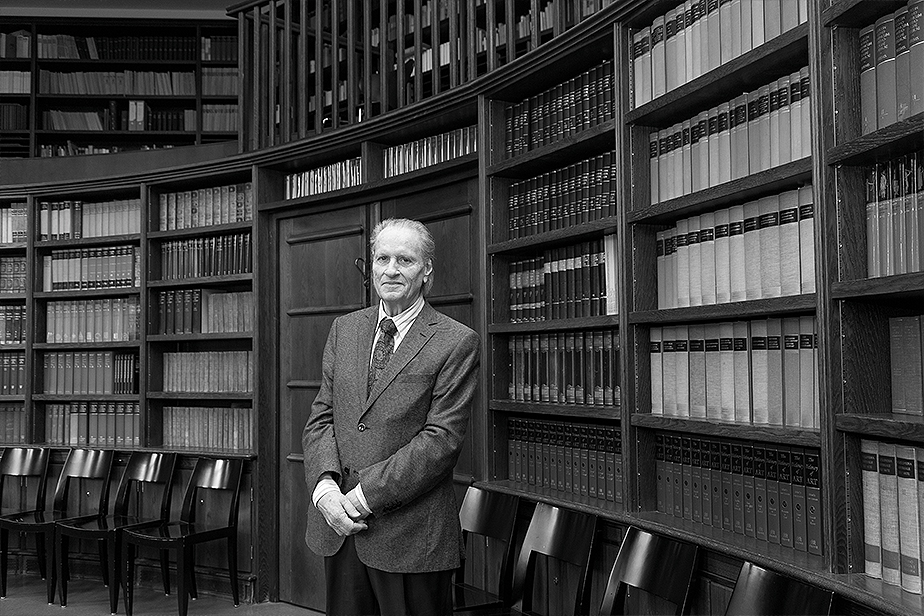

Tireless bridge builder Martin Warnke (*1937)

Professor of art history from 1978 to 2003, Warnke strove to honor the origins of his field in Hamburg. He successfully advocated for the repurchase of the Warburg-Haus, restoring it to a place of scholarship. He also set up the Centre for Political Iconography, which has links to Warburg’s work.

Universität Hamburg, Foto: Michel Dingler

Martin Warnke in the reading room of the Warburg-Haus, 2017

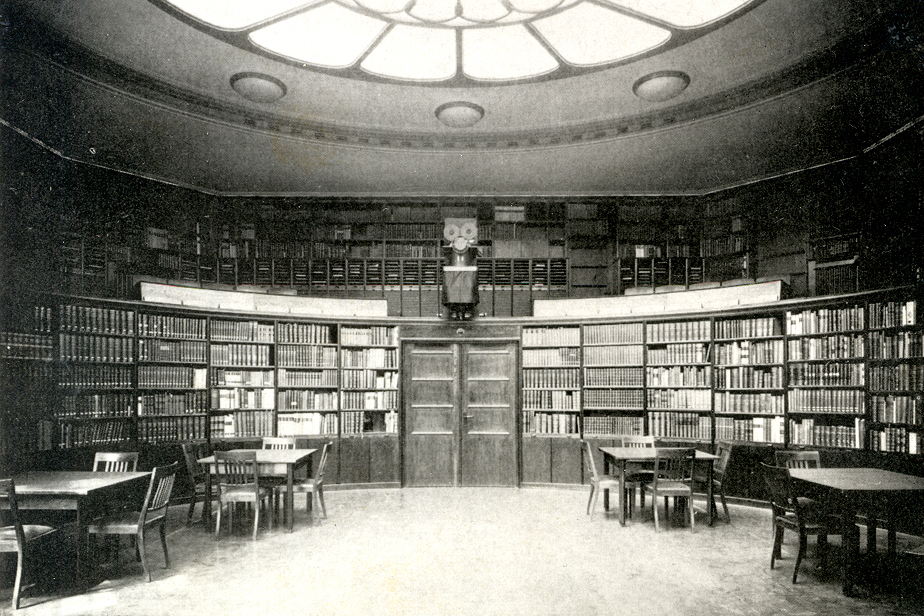

A system according to the “law of good neighbors”

In Aby Warburg’s semi-public private library, the books were not arranged alphabetically but by topic. For Erwin Panofsky, the collection – 60,000 volumes at last count—and the exchange with Warburg were a great source of inspiration for his own work. In 1933/1934, the library transferred to London and Panofsky fled to Princeton—for both, a permanent move.

Warburg-Institute Archive, London

Reading room of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, 1926

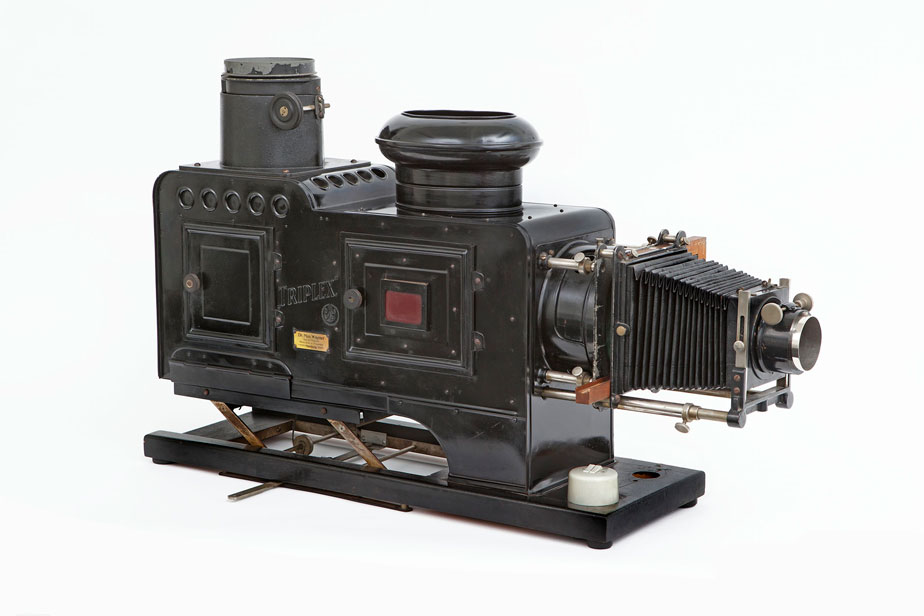

Two-in-one

This device, most likely used by Panofsky, was both a slide projector and overhead projector. It could project large slides, photos, and pictures from books—a handy tool at a time when limited resources made it difficult to procure material for teaching purposes.

Universität Hamburg, Kunstgeschichtliches Seminar, Mediathek, Foto: Plessing/Scheiblich

Triplex epidiascope (without mirror and objective) from the Art History Seminar, Müller-Wetzig, ca. 1925

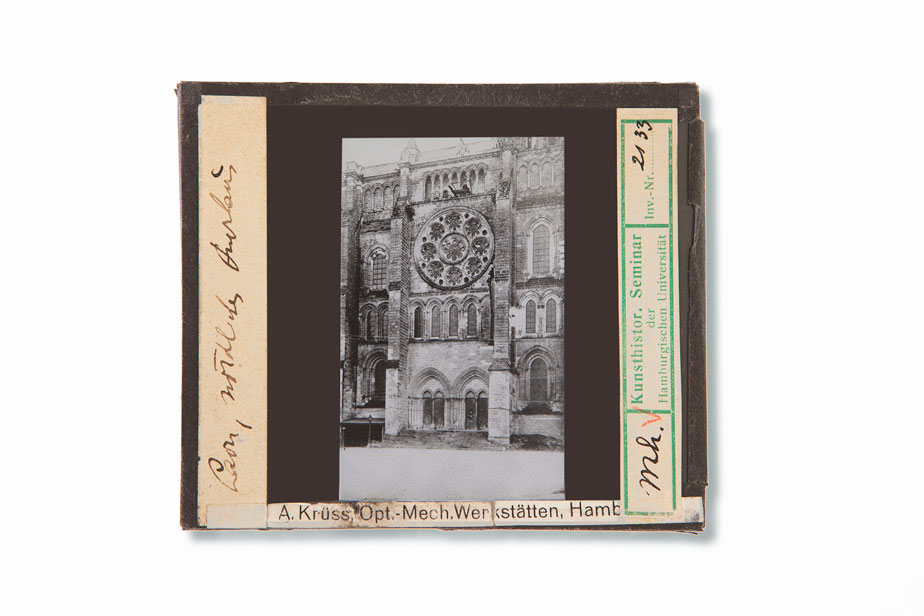

DIY

Like many others, Panofsky had to label this glass slide, presumably from a lecture on the Gothic period, himself. In 1926, when he was appointed to the long-awaited chair of art history, he is rumored to have quipped that he had been an assistant without a professorship and was now a professor without an assistant.

Universität Hamburg, Kunstgeschichtliches Seminar, Mediathek, Foto: Plessing/Scheiblich

A large slide labeled by Panofsky: “Laon, northern transept”, 1920s

Understanding an artwork in three steps

Panofsky’s three-step model—formal description of the picture, iconographic analysis of the picture’s motifs and symbols, and an iconological interpretation—was conceived above all to sharpen the student’s sense of an artwork’s various layers of meaning. He developed this approach in Hamburg but he only became famous after publishing in the United States.Transcript from an exercise taught by Erwin Panofsky, William Heckscher, 1932

A picture says more than a thousand words

The Research Centre houses roughly two-hundred thousand flash cards for more than 100 key words. The special library for these cards is also organized according to these key words. It is an ideal place to investigate the main topics, symbols, and intentions of political images from antiquity to the present.Picture index on political iconography, 1993 (1st edition)

Selection on flash cards for the key word "gestures", from 1991;

Interpreting the power of images

This manual, which grew out of the work on the picture index of political iconography, helps us decode the language of images. Roughly 150 richly illustrated articles explain the origins, transformations, and effects of political motifs.Martin Warnke, Uwe Fleckner, Hendrik Ziegler, Eds., Handbuch der Politischen Ikonographie, Vol. 1 and 2, 2011

Hamburg’s first female professor

In 1926, the Faculty of Philosophy established an extraordinary professorship for lower German linguistics, to which it sought to appoint Agathe Lasch. The Faculty had to justify to the skeptical education authorities why it “could not do otherwise […] than to suggest a female faculty member for the position in this exceptional case.”Article by Prof. Dr. Agathe Lasch, Hamburger Nachrichten, 4 January 1927

Passionate language researcher: Agathe Lasch (1879–1942)

As extraordinary professor and co-director of the German Seminar from 1927, Lasch was able to afford an apartment with a separate office. Her workload was enormous. In addition to her research and teaching obligations, Lasch continued to supervise a dictionary for Hamburg and Middle Low German terms.

Satu Helomaa, Kauniainen, Finnland (aus dem Nachlass von Martta Jaatinen)

Agathe Lasch in her apartment in today’s Gustav-Leo-Straße 9, 1930

Bursting “with great anticipation and great longing”

The excited experts were not disappointed. Lasch’s grammar remains a standard text on lower German philology, to which a reprint in 1974 attests. The linguist added many explanatory notes to the articles—unusual at the time—and proved the existence of the umlaut in Middle Low German.Agathe Lasch, Mittelniederdeutsche Grammatik, 1914

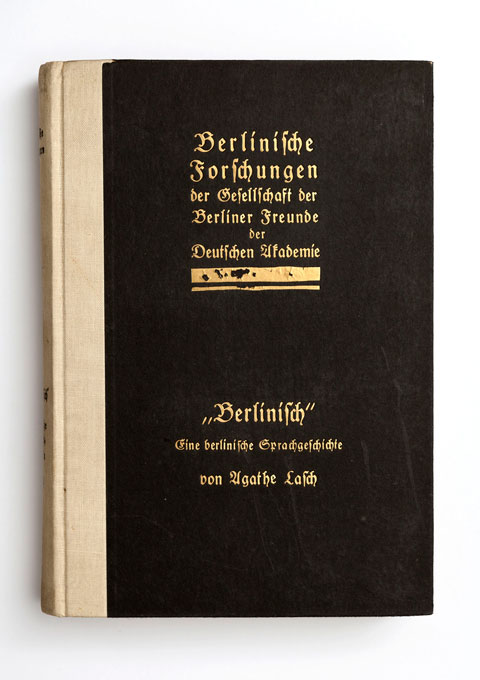

A history of her home city

This history of the spoken word in Berlin is considered the springboard of modern urban linguistic research. With her characteristic meticulousness, Lasch analyzed a huge store of material, from conversations between coachmen to the correspondence of scholars. She wrote: “Berlinish is not […] a random, unkempt mish-mash; viewed historically, it is easy to delineate.”From the source to the dictionary

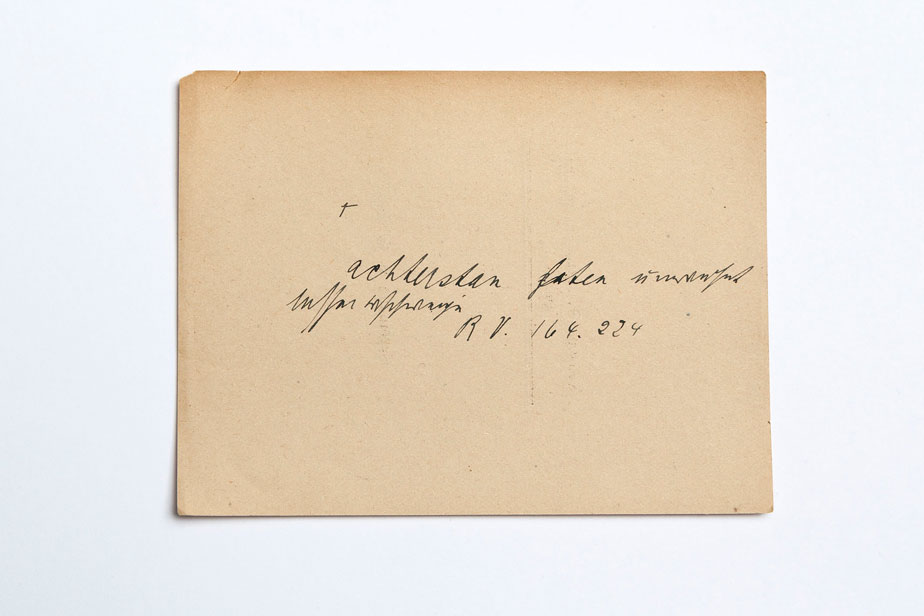

In 1923, Agathe Lasch began her extensive work on a new Middle Low German dictionary. One of her numerous sources was the Low German story Reineke, der Fuchs (Reynard the Fox). This story, as Lasch noted, contained the word “achterstan” in lines 164 and 224. Alongside many others, the meaning of the word found here went into the “achterstan” entry in the first dictionary edition of 1928. At the time, there were over 55,000 of these kinds of notes.

Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik, Foto: Plessing/Scheiblich

Lasch and Borchling, Eds., Mittelniederdeutsches Handwörterbuch, first delivery, “a” through “attik.” 1928.;

Evidence of Achterstan in A. Lasch’s handwriting, 1920s; F. Prien, Ed.,

Reinke de vos, 1887;

Reference work and research tool

From the 13th to the 17th centuries, Middle Low German was the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League. The dictionary, which continues to be updated today, is an important resource for historians, linguists, researchers in literary studies, and in many other subject areas.Ingrid Schröder, Ed., Mittelniederdeutsches Handwörterbuch, 41st delivery, Vol. III, Part 3, 2019