Responsibility

Responsibility

Like all other German universities, ours was complicit in National Socialism. After 1945, many Germans wanted to forget the recent past. Thus, nobody in Hamburg or at other universities was taking a critical look at what had happened. It was only fifty years after the National Socialists took power that the University management felt compelled to have its own National Socialist past closely examined. Nonetheless, it was one of the first universities to assume responsibility for its past— thanks to the efforts of a new generation of students. Studying at the end of the 1960s, they began to question how fellow Germans remembered the Nazi past and the role of their own professors. Thus, they paved the way for a long-overdue reckoning and culture of memory.

Tight-lipped about the past

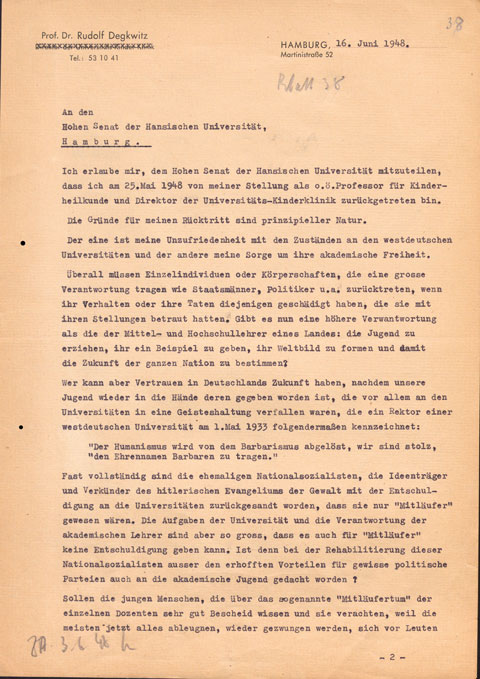

Up through the 1960s, a generation of professors, not a few of whom had begun their own careers under the National Socialists, shaped the way the people saw the past. Only a handful of those academics who had been hounded into exile chose to return. On the other hand, professors who had had ties to the National Socialists or initially been suspended following the war were quickly rehabilitated. One of the few who openly opposed this practice was the Hamburg professor of medicine Rudolf Degkwitz. When he called for radical denazification in 1948, he was ignored.

HStA; Bestand Conti-Press

Students frame the memorial plaque with red carnations, 1971

The university works through its history

All departments took part in the Hamburg research project on the history of the University under National Socialism. More than fifty academics from the University researched the history of their respective disciplines, creating a nuanced portrait of daily life at the University in the Third Reich. In 1991, the results were presented in a 1,500-page publication and public exhibition. The project led to the Center for the History of Universität Hamburg, a series of papers, and the naming of lecture halls after persecuted academics.“Germany’s first national socialist university”

National Socialism profoundly changed the University and inspired very little or noteworthy opposition. For example, the University’s self-governing bodies were replaced by the “Führerprinzip” and the University publicly presented itself as “Germany’s first National Socialist University.” The Civil Service Restoration Act allowed the University to let go of over ninety of its members, including prominent scholars, for “racial” or political reasons. Significant areas of research thus lost in importance. Instead, new politically motivated fields such as the biology of race or military science took their place.Opposition to the reinstatement of Nazis

With this letter, Rudolf Degkwitz announced his resignation as professor of medicine and director of the Eppendorf Children’s Hospital. He resigned to protest the lack of de-Nazification measures at the University. He himself had been accused of sedition by the Nazis in 1944.

Universität Hamburg, HStA, Universitätsarchiv, 361-6_IV 166

Letter from Prof. R. Degkwitz to the High Senate of Universität Hamburg, 16 June 1948, facsimile

The university’s position

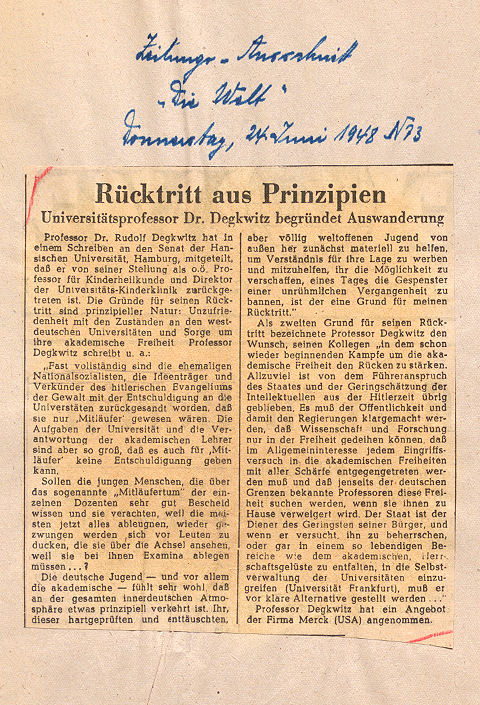

The University and the higher education authority debated the appropriate reaction to Degkwitz’s letter. It had caused a public stir when the press reported on it under the title “Resignation on Principle.” Ultimately, the University leadership went no further than to distance itself from Degkwitz.Reply from the University rector to Prof. R. Degkwitz, facsimile

Universität Hamburg, Universitätsarchiv, HStA 361-6 IV 166

Professor Degkwitz explains his emigration. Newspaper excerpt from "The World" June 24, 1948

Failure to confront the past

Even as late as 1969, the University had still largely remained silent about the Nazi era. In an anniversary publication, the true reasons for the dismissals of 1933 were concealed. University instructors such as William Stern did not by any means “retire.” They were dismissed because they were Jewish.Universität Hamburg 1919–969, Universität Hamburg

Letter from William Stern to the University leadership, 27 April 1933, facsimile

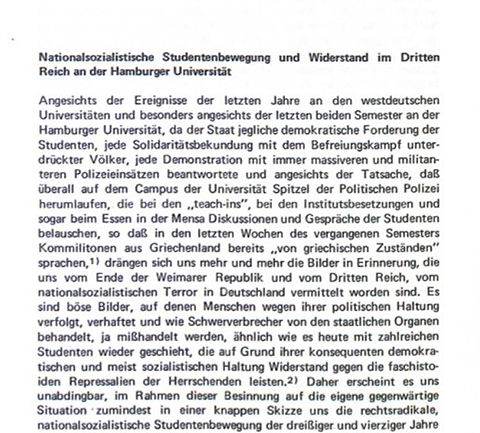

Students strike a raw nerve

The University student council, ASta, published a refutation to the Festschrift in 1969. Students contributed articles about the University’s National Socialist history and demanded that the issue be confronted.Das permanente Kolonialinstitut. 50 Jahre Hamburger Universität, 1969

Universität Hamburg, Zentralstelle für wissenschaftliche Sammlungen. S. 139- 153

National Socialist Student Movement and Resistance in the Third Reich at the University of Hamburg, from: The permanent colonial institute. 50 years Hamburg University, 1969

Investigation of Nazi-era history

In 1982, at the urging of the City and University leadership, scholars at the University began a nine-year investigation of the University’s history between 1933 and 1945. This project initiated and laid the groundwork for further studies of the University’s history during the Third Reich.Eckart Krause, et.al. Ed., Hochschulalltag im „Dritten Reich“, Volumes 1–3, 1991

Enge Zeit exhibition

The results of the investigation about the University in the Nazi era were not only presented to the public in a book. They were also on display in the exhibition ENGE ZEIT, opened in 1991 in the Audimax. The exhibition centered on University members who were exiled and persecuted.

Universität Hamburg, Arbeitsstelle für Universitätsgeschichte, Foto: Plessing/Scheiblich

Angela Bottin, ENGE ZEIT, exhibition catalog, 1991

An in-house series for academic history

What began as a plan to publish the results of the investigation into the Nazi-era history of the University led to the formation of the University’s own publication series in 1986. It is overseen by the Center for the History of Universität Hamburg, and has published twenty-six volumes. Topics range far beyond the Nazi era.Hamburger Beiträge zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, 26 volumes, 1986–2019

Presentation to the public

Concurrently with the opening of the exhibition, the three-volume Hochschulalltag im ‘Dritten Reich’ (University Life in the “Third Reich”) was introduced to the public. Speakers at the event included the sociologist Lord Ralf Dahrendorf from Oxford and Hamburg’s second mayor Ingo von Münch.Opening of the exhibition ENGE ZEIT, speaker Ingo von Münch, 1991; Eckart Krause presents the three volumes of Hochschulalltag im ‘DrittenReich,’ 1991

A dramatic staging

The 102 tall metal columns that held the objects from the exhibition ENGE ZEIT stood close together on the stage of the Audimax, reminiscent of marching troops. The background soundtrack with sounds of marching and a light design that simulated the movement of waves intensified the impression.View of the exhibition ENGE ZEIT, 1991

A memorial plaque for members of Hamburg’s White Rose

In 1971, at the urging of the student council, the University finally signaled its willingness to commemorate the years between 1933 and 1945. There is a floor plaque in the Audimax, commemorating students murdered by the Nazis. They actively opposed the Nazi state and were closely affiliated with the White Rose in Munich.Students frame the memorial plaque with red carnations, 1971

Students put on the pressure

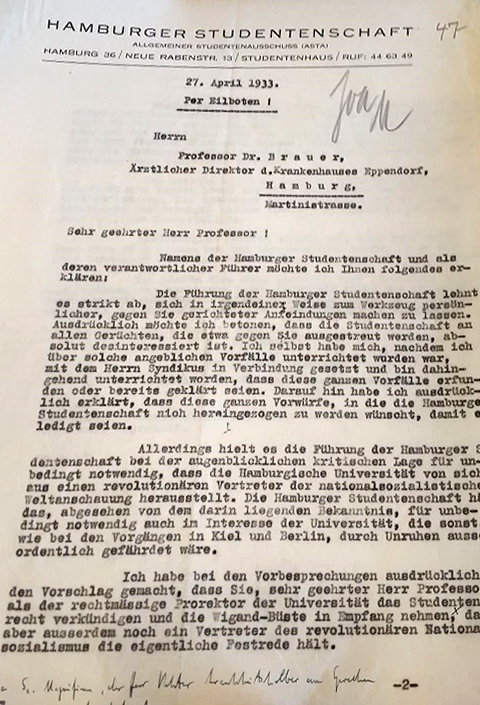

Starting in 1931, the National Socialist German Students’ League made up nearly forty percent of AStA, the student council. By 1933, the League had become the prime mover in the efforts to enforce political conformity at the University. It demanded the dismissal of Jewish instructors, and the University complied by forcing them to cancel their lectures.Letter from the League’s University Gruppenführer to Senator F. Ofterdinger, 12 April 1933, facsimile

Restructuring the university

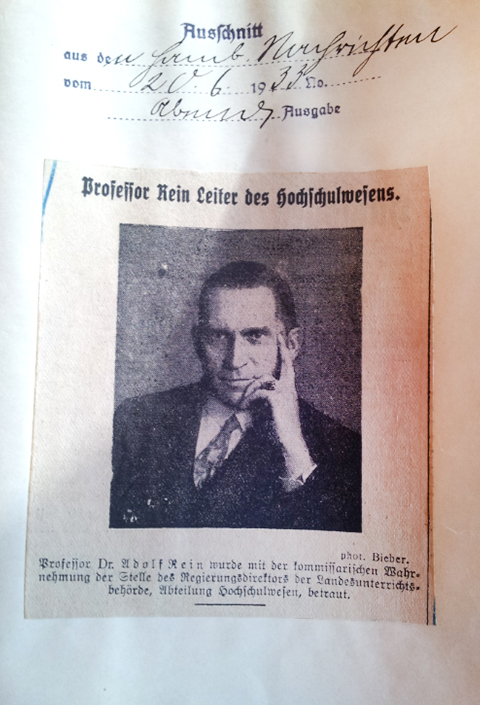

As rector, Adolf Rein moved forward with the restructuring of the University between 1934 and 1938. However, due to internal rivalries, the professor of colonial history was unable to implement all of his plans. His “political college,” for example, in which he intended to coordinate political indoctrination with Nazi organizations, never came into being.Organizational chart for the structure of a political college by A. Rein, 1933

Universität Hamburg, Universitätsarchiv, HStA 361-6 IV 1161, Bd2, Beiakte 5, 6

Newspaper clipping on the appointment of Adolf Rein to the post of Head of Higher Education at the State Teaching Authority; Hamburger News 20.6.1933

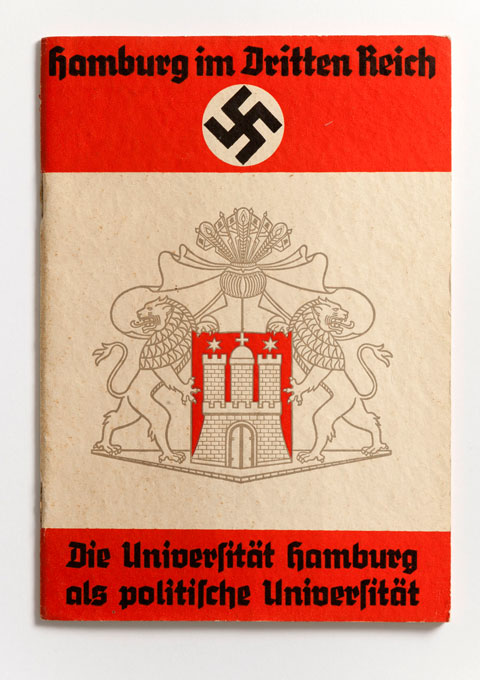

The idea of a “political university”

After 1933, Rein took the lead in restructuring the University. He had made a name for himself in 1932 with his plans for changing the University to conform to Nazi ideals. He pursued the idea of a “political university,” in which scholarship would be subordinate to political principals.

Universität Hamburg, Arbeitsstelle für Universitätsgeschichte, Foto: Plessing/Scheiblich

Adolf Rein, Die Universität Hamburg als Politische Universität, 1935

A new faculty?

A “political association of the faculties” first founded in 1933 was designed to prepare a curriculum for political classes. It was to be given the rank of a faculty and thus have its own dean’s chain of office. The new faculty never became a reality, and therefore this medallion remained a preliminary design.

Universität Hamburg, Arbeitsstelle für Universitätsgeschichte, Foto: Plessing/Scheiblich

Prototype of the dean’s medallion for the “political association,” design: Carl Otto Czeschka, 1936

Traditional vs. political symbolism

The University’s four original faculties’ chains of office for the deans in 1921. The symbols used in their design had a long tradition, some reaching back to antiquity. The 1936 medallion for the new political faculty, on the other hand, used the new political symbol of the swastika.Willingness to conform

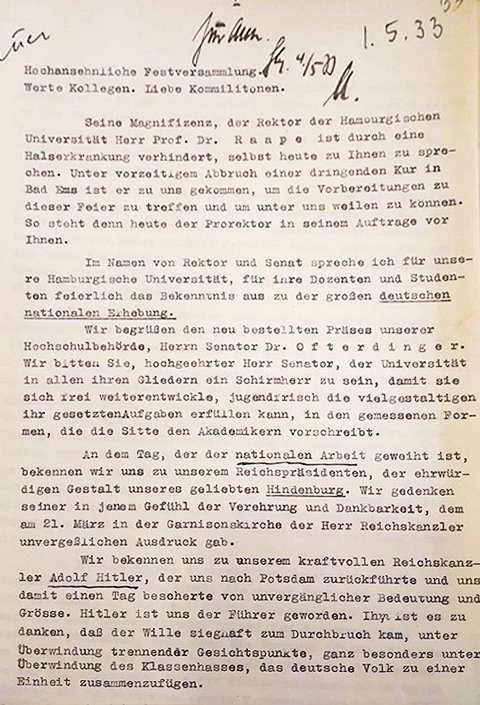

Even though only few professors were members of the Nazi Party in 1933, many of them agreed with the broader goals of the new regime. They hoped to see a national upswing and to overcome the tribulations of the Weimar Republic. They adapted quickly to the new circumstances and accepted the dismissals of colleagues without complaint.Ceremony in the University auditorium, 1 May 1933

Pioneer of national socialism

Adherents of Albert Wigand, who died in 1932, regularly held memorials at his bust during the Nazi era. The meteorologist, who propounded National Socialist ideology, was rector of the University in 1931–32. His bust stood in the foyer of the Main Building until 2007, when students toppled it.

Universität Hamburg, Arbeitsstelle für Universitätsgeschichte, Foto: Plessing/Scheiblich

Albert Wigand, bust by Hans Schmitt, 1932

A gift for the university

The Hamburg student body presented the bust of Albert Wigand to the University at a ceremony on the Day of National Labor, 1 May 1933. Wigand was a supporter of the Nazi students. He is reported to have said he would “lead his students into a riot with banners flying.”Article in the Hamburger Nachrichten newspaper, 26 April 1933, facsimile

Nazi student leaders demand new university

Wolff Heinrichsdorff was AStA president and “Führer of the Hamburg student body” beginning in late April 1933. In his speech at the celebration of national labor on 1 May 1933, he attacked the traditional university and demanded a radical change to a political university and the adoption of National Socialist goals.Speech by Wolff Heinrichsdorff at the celebration of national labor on 1 May 1933 (reenactment)

Universität Hamburg, Universitätsarchiv

NS student leader calls for new university. Letter from the Hamburg student Union to Professor Dr. Brauer, Hamburg 27.04.1933

Commitment to national socialism

The University declared its commitment to the “national revolution” and to Adolf Hitler on 1 May 1933. The National Socialist Students’ League demanded that extraordinary professor Adolf Rein be the main speaker at the event. Prorector Ludolph Brauer was relegated to the sidelines.Program for the ceremony on 1 May 1933, facsimile

Staatsarchiv A.170.8.15, S.33-35

Confession to National Socialism. Speech paper by Vice-Rector Professor Dr. Brauer. State Archives A.170.8.15, p.33-35

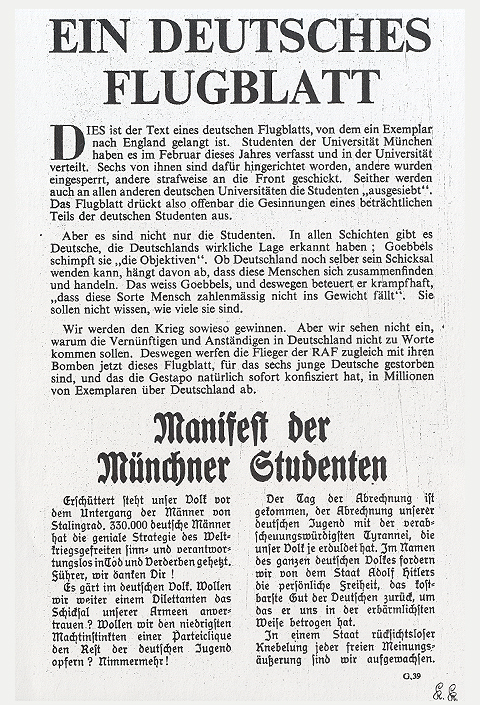

The Hamburg White Rose

In the early 1940s, several, primarily young, Hamburg residents formed informal groups in opposition to the Nazi regime. Many of them were students at the University. Arrested in 1943–44, some died in prison. Hans Leipelt was executed. The name “Hamburg White Rose” was given to them retroactively.Student ID cards of members of the Hamburg White Rose

Universität Hamburg, Arbeitsstelle für Universitätsgeschichte

Leaflet of the "White Rose", the student resistance from Munich. The leaflet also circulated in Hamburg.

Universität Hamburg, Arbeitsstelle für Universitätsgeschichte

Hamburg student Hans Leipelt was murdered by the National Socialists. From: Angela Bottin, Enge Zeit, 1991